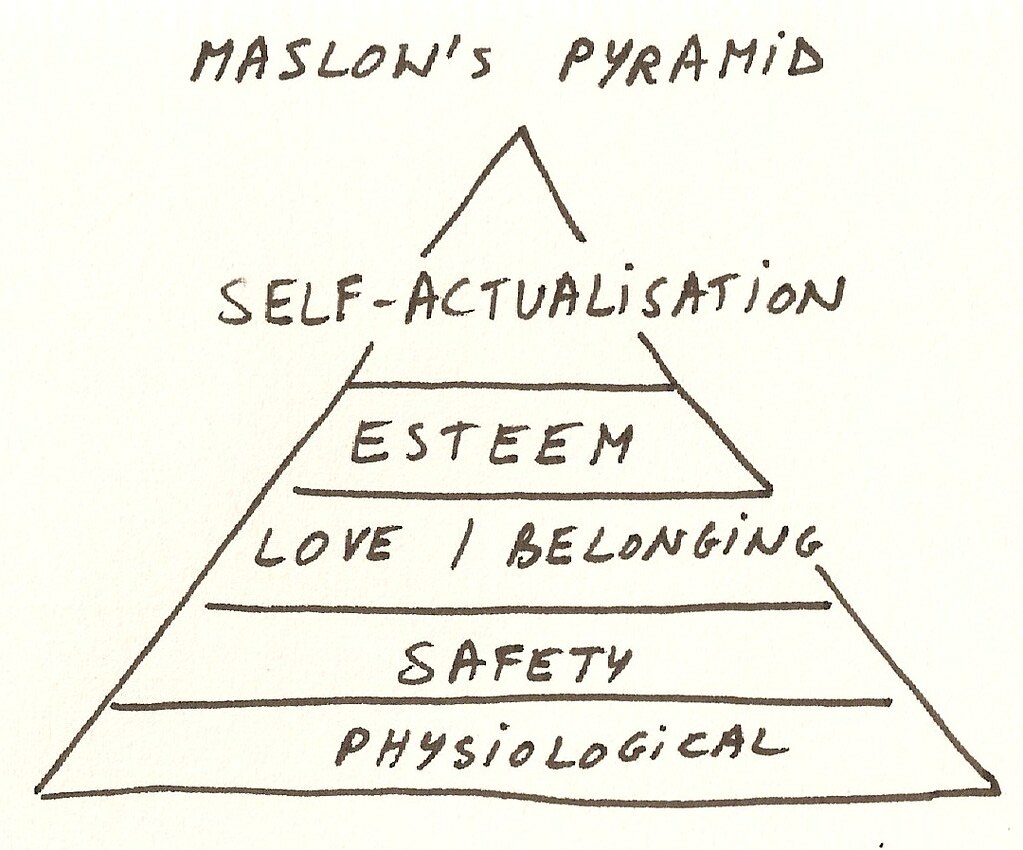

Many of you may be familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Developed in the 1940s, it is a theory of psychology that models human needs and motivations. Like any good theory, it’s rather simple and resonates with our lived experiences. It suggests that our basic needs, those lower down in the hierarchy, have to be taken care of before we can devote time and energy to psychological needs. Have you ever tried to engage in idle chit-chat while you were hangry? Then you get the point. Continuing, one’s psychological needs must be taken care of before one can attend to self-fulfillment needs. Think of how many successful creatives, innovators, and entrepreneurs have strong networks of social support. For more than 70 years, variations of this theory have been used to describe a range of human behaviors, motivations, and emotions and have been widely adopted in business, management, marketing, sales, and other enterprise settings.

In this post, I want to discuss what Maslow’s theory might teach us about fear.

Unpacking Fear

Fear is a natural, necessary, and powerful human emotion. I think all of us can personally attest to that power. As I consider times in my life when I have been deeply afraid, whether that fear was justified or totally irrational, my experiences of those fears were entirely genuine. Those experiences were immediate, visceral, and all-consuming. I flinch, even from the memories of those moments, because the experience of fear and the loss of control I associate with that experience is so unpleasant. I am not unique. In fact, my fear responses are an indication that I am a relatively healthy human being.

Fear involves two basic mechanisms; a biochemical response that is nearly universal to our species–also known as “fight or flight”–as well as individual emotional responses that alert us to the presence of threats, danger, and potential physical or psychological harm. The two often happen in conjunction, as one triggers the other. But while most of us intimately understand the emotional complexities of our fear, the specific physiological effects are more difficult to pin down.

In general, fear triggers the slowing or complete shut down of biological functions that are not needed for survival (e.g. digestion) and sharpens or increases functions that might aid survival (e.g. cardiovascular and respiratory functions). More relevant to this blog post, Harvard researcher, David Ropeik, reports that fear can also interrupt brain functions that allow us to regulate emotions, read non-verbal cues, consider before acting, and to act ethically. We are left susceptible to intense emotions and impulsive reactions and rendered (at least partially) incapable of sound and appropriate decision-making. This may actually suit us well in times of threat when indecision may have life-threatening consequences. But what happens when we have chronic fear in scenarios that are not life and death matters?

Interrogating Our Fear Networks

I want to ask you to consider the role of fear in your own life, particularly during your formative years. Create a mental catalog of what you were explicitly taught to fear and what you learned to fear as a result of implicit socialization–from family, friends, school classmates, sports teammates, church congregations, books, television, films, and more. Got it?

The result represents what I call a “fear network.” It is something that has continuously evolved as you have aged and experienced life. It is meant to keep you safe and to protect you by raising red-flags in contexts that could potentially cause you harm. Now, I want you to consider how this fear network has served you in the past. I will be brutally honest and say that my own fear network has, on many occasions, served me well . On many others, my fear network has been the cause of needless suffering and cruel decision making.

Fear Networks and Bias

Now imagine that an entire group of people was a significant part of your fear network–black people, police officers, gay men, people dealing with homelessness, people living with mental illness, impoverished people. I’ll offer some brutal honesty once again. More than one of the groups of people I just mentioned were parts of my fear network as a young person in spite of the fact that my rational mind, observable facts, and common decency told me that this was wrong. I am fortunate that I was an adaptable young person and that I had some wonderful mentors in my life.

For those whose fear networks have become deeply entrenched into adulthood, the internal conflict of recognizing these kinds of biases in oneself can be profound. Current psychological research demonstrates that most people will go to extraordinary lengths (even unconsciously) to resolve internal conflicts, or cognitive dissonance. So…what happens when someone’s expressed beliefs (for example, “I treat everyone the same regardless of their outward physical traits”) and unconscious behaviors (my physiological fear response is activated when I am in proximity to certain individuals) are not in sync? Here are a few possible responses:

- Lean into my perception of feeling “threatened” in order to justify my fear.

- Adopt the belief that I would not be experiencing fear unless the threat was objectively and undeniably real.

- Surround myself with a community of people whose fear networks are similar to mine, resolving my inner conflict by overwhelming it with and external chorus of consensus.

These are responses I have seen in friends and strangers alike over the last two weeks. I have seen them used to justify the presence of both black men (predominantly) and police officers (to a far lesser degree) in the fear networks of enormous numbers of people. And though the two groups of fearful people that I just mentioned seem as if they could not be more different, they have some very basic things in common. First, these responses are infinitely easier than dismantling the fear network that has protected them since childhood, that was built (at least in part) by those who love them most, and that has driven their behavior on a deeply elemental level. Second, these responses are ways to avoid confronting the fact that some of their automatic and deeply genuine fear responses are not just based on past experiences and credible accounts, but also upon on unfounded assumptions and generalizations. Finally, all of these responses are made very dangerous when combined with the biochemical effects that fear has on our thoughts and perceptions (inability to regulate emotions, read non-verbal cues, think before acting, or act ethically).

Returning to Maslow

Thinking about social justice advocacy and education as stewarding another person through the experience of fear has shifted my approach to that work significantly. I find myself asking, “What is the most effective way to inspire people to do the deeply personal, difficult, and vulnerable work of troubleshooting their fear networks and overcoming what may be a lifetime of deep-seated fears?” Though they are the favorites of social media users everywhere, hostility and shaming seem to be particularly ineffective strategies in this type of education.

If Maslow’s Hierarchy presents us with five core human needs, it follows that each need would produce a corresponding fear of the condition when that need is not met.

- Fear of Regret (Self-Actualization Needs) – The fear that we will look back at our lives and see that we have not achieved our full potential.

- Fear of Failure (Esteem Needs) – The fear that we will not be recognized for our accomplishments or that we will lose prestige.

- Fear of Isolation/Rejection (Belonging Needs) – The fear that we will lose important relationships and group membership.

- Fear of Injury & Suffering – Fear that we will lose the means of safety and security.

- Fear of Illness & Death – Fear that we will lose physiological necessities.

These fears not only populate our fear network, they may additionally be fears that we associate with letting go of our fear networks. For example, the woman who has for a lifetime been socialized to be afraid in situations when she must interact with black men alone, may experience fear of injury and suffering when she interacts with a new coworker (even though she knows this to be an unfounded fear). However, the prospect of giving up that fear may spark a new fear of isolation, as her friends may find her newfound willingness to interact with “scary” people to be alarming.

On Compassion and Fear

The example above was intended to make the point that fear is a complex motivator that operates in multiple ways on our bodies and minds. It wasn’t intended as an excuse or an absolution of responsibility. To be clear, I believe if you discover yourself to be in possession of a f*cked up fear network, it is your ethical responsibility to do the work to unf*ck it.

However, understanding the nature of fear, how it is part of our socialization, how biases against groups of people can manifest as fears, how it is connected to our basic needs and motivations, and how fear alters our biochemistry and cognition inspires me to be more compassionate about my approach. Social justice education is less like shaking people until they wake up and “get it” and more like coaching someone to quit smoking cigarettes after a 20-year, pack-a-day habit. Some people really can go cold turkey, but for most, the process will be a struggle that touches every part of their lives.